Dr. John Montanee: Father of New Orleans Voudou

Doctor John Montanee is the Father of New Orleans Voudou, the loa of drummers and rootdoctors, and patron to male Voudou practitioners and female rootwomen. Not much was written about his life prior to the recent publication of Dr. John Montanee: A Grimoire by Louis Martinie, a book that promises to be highly influential in documenting the evolution of New Orleans Voudou in the twenty-first century. I am honored to have contributed a couple of essays to the grimoire and the following several paragraphs are excerpted from one of the articles I wrote, The Superposition of Dr. Jean A Handwriting Investigation. The article describes my experiences with Dr. John as a teenager and then culminates in an analysis of his handwriting in an effort to learn more about him. The article can be read in the book or online in its entirety here.

After examining Dr. Jean’s signature, I suggest that he (Dr. John) was a driven and industrious man, who had a desire to not only do well and adjust to the events of his life - as someone who was stolen, sold as a slave and forcibly moved to a different country (Cuba) as a result – but, to do exceedingly well. He no doubt suffered from terrible trauma, and his way of dealing with it was to master whatever task it was he was told to do. It is said he was either a Bambaran prince or the son of a Bambaran prince, and if this is the case, the effect on him, his ego, and his sense of importance would have been devastating on a different level than someone who was not a leader with a huge responsibility to his community. I am not suggesting that his trauma would be more than another African stolen from their family and homeland, just different with an additional layer.

Sometimes when a person becomes legendary they cease to be human beings and instead become the legend themselves. Dr. Jean is remembered according to his legend, as a powerful gris gris man who was rich, got a lot of women and who was the teacher of Marie Laveaux. The whole context of the trauma of the Diaspora is left completely out of his-story, and this is not only unfortunate, but it is highly disrespectful. My belief is that his goal from the onset of becoming a slave would have been to reclaim his personal power and power within the community (whatever community he ended up in), and to do so using his strength and charisma. This internal fortitude was enough to achieve his eventual freedom from slavery; it is said that his West Indian master taught him to be an excellent cook and grew quite fond of him, and eventually gave him the gift of freedom. As a result, Dr. Jean left Cuba to be a cook on a ship and eventually ended up in New Orleans where these characteristics of strength, charisma and fortitude landed him as a gang leader of cotton rollers. Within that community, he began to be known for his apparent supernatural powers and fortune telling abilities. This set the tone for his eventual great success in New Orleans. All through the various narratives of his-story, we can see his ability to transcend the normal performance of a given task and exceed all expectations.

Dr. Jean was likely a man who liked to make grand entrances in an effort to make his presence known. But, he more than likely retreated from this showy demeanor to a very warm and gregarious human being. People probably liked him more than not and he likely had many friends, and at least as many acquaintances. He would have been someone who would have started a family as soon as possible and given the culture from which he came, would likely have had more than one wife and many children. Family would have been very important to him and he would have taken his role as provider very seriously – yet another mechanism to drive his entrepreneurial spirit.

In addition to being successful in his various jobs and as a provider, he would have taken his role as a leader of the Voudous quite seriously, as well. As gris gris is a religiomagical system originating in Senegal and practiced by the priests, it makes perfect sense that he would have brought knowledge of the tradition with him to New Orleans. Gris gris is one of the most unique characteristics of New Orleans Voudou and a tradition that persists to this day - his contribution to the New Orleans religion is unsurpassed. He expected to be noticed and he was, as his legacy lives on in the heart of the Mysteries and can be heard and felt in the beat of every drum.

Beyond his need for recognition and the importance of his role in the development of New Orleans Voudou as we know it today, he would have also been a great healer. He was connected to others on a personal level and would have had a genuine concern for their wellbeing. He would have helped people who asked, and would have also figured out how to make money doing the very thing that created an air of mystique around him. Thanks to Dr. Jean and Marie Laveaux, New Orleans Voudou and Hoodoo continues to afford many people the opportunity to make a living today, as it did in the past.

Working with Dr. John

To begin, it is best to not petition Dr. John for any favors. Simply give him some offerings and begin developing a relationship with him. When he makes his presence known to you through dreams, visions and physical manifestations, then it is appropriate to begin asking him for favors.

Offerings to Dr. John

- Absinthe

- graveyard dirt from St. Roche (general dirt from the graveyard as opposed to any sort of dirt from a particular grave will work)

- High John root

- Low John Root

- percussion instruments

- drums

- water from Bayou St. John

- Earth from Bayou St. John

- Earth from Congo Square

- Red Brick Dust

- healing herbs and roots in general

- gris gris

The above dirts, roots and curios can be used to create a variety of conjures and in petitions to Dr. John as well. I recommend creating conjures on one of the Voudou veves for drumming. Use the rada for cool, balanced conjures and petro for hot, tempestuous conjures. Visit the Some Conjures page on drjohnvoodoo.com for more guidance and ideas, including how to make Magick gris gris lamps.

Note that in the Dr. John Montanee Grimoire, Louis Martinie describes an elixir he created for Dr. John that calls for consecrating two Hi John roots "with Elixir of Red Lion and White Eagle (Culling - GBG)." For those unfamiliar with the alchemical literature, Louis T. Culling was Grandmaster of an occult lodge called the G.B.G. (Great Brotherhood of God) who authored a Manual of Sex Magick that contained codes for describing alchemical processes. The main terms in the code and their translations are as follows:

RED LION - the male Alchemist, or his penis.

WHITE EAGLE - the Alchemist's mate, or her vagina.

RETORT - the vagina and/or womb.

TRANSMUTATION - (or transubstantiation) an altered state of consciousness.

ELIXIR - the semen.

The Chariot of Antimony by Basil Valentine (1642) contains the following description of the Lion and Eagle of Alchemy:

RED LION - the male Alchemist, or his penis.

WHITE EAGLE - the Alchemist's mate, or her vagina.

RETORT - the vagina and/or womb.

TRANSMUTATION - (or transubstantiation) an altered state of consciousness.

ELIXIR - the semen.

The Chariot of Antimony by Basil Valentine (1642) contains the following description of the Lion and Eagle of Alchemy:

Let the Lion and Eagle duly prepare themselves as Prince and Princess of Alchemy - as they may be inspired. Let the Union of the Red Lion and the White Eagle be neither in cold nor in heat ... Now then comes the time when the elixir is placed in the alembic retort to be subjected to the gentle warmth.... If the Great Work be transubstantiation then the Red Lion may feed upon the flesh and blood of the God, and also let the Red Lion duly feed the White Eagle – yea, may the Mother Eagle give sustain-molt and guard the inner life.'

Thus, in Louis' description of his conjure water for Dr. John, the two Hi Johns are anointed with the sperm and vaginal juices of the conjurer and his or her partner, or touched by the penis and vagina, harnessing the power of male and female creative energies and balance as a primary ingredient in any conjure cure (note this is my personal interpretation of the conjure and may not be entirely accurate).

The inclusion of sex magick with Dr. John conjures makes sense when viewed within the context of his life as a man with many children, multiple wives, healer and manager of a brothel during his lifetime.

The inclusion of sex magick with Dr. John conjures makes sense when viewed within the context of his life as a man with many children, multiple wives, healer and manager of a brothel during his lifetime.

The Last of the Voudoos

by Lafcadio Hearn

from An American miscellany, vol. II, (1924)

originally published in Harper's weekly, November 7th, 1885

from An American miscellany, vol. II, (1924)

originally published in Harper's weekly, November 7th, 1885

In the death of Jean Montanet, at the age of nearly a hundred years, New Orleans lost, at the end of August, the most extraordinary African character that ever gained celebrity within her limits. Jean Montanet, or Jean La Ficelle, or Jean Latanié, or Jean Racine, or Jean Grisgris, or Jean Macaque, or Jean Bayou, or "Voudoo John," or "Bayou John," or "Doctor John" might well have been termed "The Last of the Voudoos"; not that the strange association with which he was affiliated has ceased to exist with his death, but that he was the last really important figure of a long line of wizards or witches whose African titles were recognized, and who exercised an influence over the colored population. Swarthy occultists will doubtless continue to elect their "queens" and high-priests through years to come, but the influence of the public school is gradually dissipating all faith in witchcraft, and no black hierophant now remains capable of manifesting such mystic knowledge or of inspiring such respect as Voudoo John exhibited and compelled. There will never be another "Rose," another "Marie," much less another Jean Bayou.

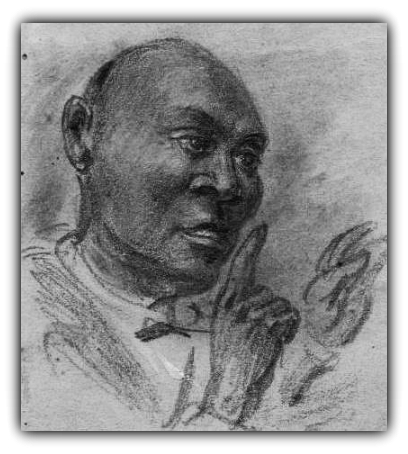

It may reasonably be doubted whether any other negro of African birth who lived in the South had a more extraordinary career than that of Jean Montanet. He was a native of Senegal, and claimed to have been a prince's son, in proof of which he was wont to call attention to a number of parallel scars on his cheek, extending in curves from the edge of either temple to the corner of the lips. This fact seems to me partly confirmatory of his statement, as Berenger-Feraud dwells at some length on the fact that the Bambaras, who are probably the finest negro race in Senegal, all wear such disfigurations. The scars are made by gashing the cheeks during infancy, and are considered a sign of race. Three parallel scars mark the freemen of the tribe; four distinguish their captives or slaves. Now Jean's face had, I am told, three scars, which would prove him a free-born Bambara, or at least a member of some free tribe allied to the Bambaras, and living upon their territory. At all events, Jean possessed physical characteristics answering to those by which the French ethnologists in Senegal distinguish the Bambaras. He was of middle height, very strongly built, with broad shoulders, well-developed muscles, an inky black skin, retreating forehead, small bright eyes, a very flat nose, and a woolly beard, gray only during the last few years of his long life. He had a resonant voice and a very authoritative manner.

At an early age he was kidnapped by Spanish slavers, who sold him at some Spanish port, whence he was ultimately shipped to Cuba. His West-Indian master taught him to be an excellent cook, ultimately became attached to him, and made him a present of his freedom. Jean soon afterward engaged on some Spanish vessel as ship's cook, and in the exercise of this calling voyaged considerably in both hemispheres. Finally tiring of the sea, he left his ship at New Orleans, and began life on shore as a cotton-roller. His physical strength gave him considerable advantage above his fellow-blacks; and his employers also discovered that he wielded some peculiar occult influence over the negroes, which made him valuable as an overseer or gang leader. Jean, in short, possessed the mysterious obi power, the existence of which has been recognized in most slave-holding communities, and with which many a West-Indian planter has been compelled by force of circumstances to effect a compromise. Accordingly Jean was permitted many liberties which other blacks, although free, would never have presumed to take. Soon it became rumored that he was a seer of no small powers, and that he could tell the future by the marks upon bales of cotton. I have never been able to learn the details of this queer method of telling fortunes; but Jean became so successful in the exercise of it that thousands of colored people flocked to him for predictions and counsel, and even white people, moved by curiosity or by doubt, paid him to prophesy for them. Finally he became wealthy enough to abandon the levee and purchase a large tract of property on the Bayou Road, where he built a house. His land extended from Prieur Street on the Bayou Road as far as Roman, covering the greater portion of an extensive square, now well built up. In those days it was a marshy green plain, with a few scattered habitations.

At his new home Jean continued the practice of fortune-telling, but combined it with the profession of creole medicine, and of arts still more mysterious. By-and-by his reputation became so great that he was able to demand and obtain immense fees. People of both races and both sexes thronged to see him--many coming even from far-away creole towns in the parishes, and well-dressed women, closely veiled, often knocked at his door. Parties paid from ten to twenty dollars for advice, for herb medicines, for recipes to make the hair grow, for cataplasms supposed to possess mysterious virtues, but really made with scraps of shoe-leather triturated into paste, for advice what ticket to buy in the Havana Lottery, for aid to recover stolen goods, for love powers, for counsel in family troubles, for charms by which to obtain revenge upon an enemy. Once Jean received a fee of fifty dollars for a potion. "It was water," he said to a creole confidant, "with some common herbs boiled in it. I hurt nobody; but if folks want to give me fifty dollars, I take the fifty dollars every time!" His office furniture consisted of a table, a chair, a picture of the Virgin Mary, an elephant's tusk, some shells which he said were African shells and enabled him to read the future, and a pack of cards in each of which a small hole had been burned. About his person he always carried two small bones wrapped around with a black string, which bones he really appeared to revere as fetiches. Wax candles were burned during his performances; and as he bought a whole box of them every few days during "flush times," one can imagine how large the number of his clients must have been. They poured money into his hands so generously that he became worth at least $50,000!

Then, indeed, did this possible son of a Bambara prince begin to live more grandly than any black potentate of Senegal. He had his carriage and pair, worthy of a planter, and his blooded saddle-horse, which he rode well, attired in a gaudy Spanish costume, and seated upon an elaborately decorated Mexican saddle. At home, where he ate and drank only the best--scorning claret worth less than a dollar the litre--he continued to find his simple furniture good enough for him; but he had at least fifteen wives--a harem worthy of Boubakar-Segou. White folks might have called them by a less honorific name, but Jean declared them his legitimate spouses according to African ritual. One of the curious features in modern slavery was the ownership of blacks by freedmen of their own color, and these negro slave-holders were usually savage and merciless masters. Jean was not; but it was by right of slave purchase that he obtained most of his wives, who bore him children in great multitude. Finally he managed to woo and win a white woman of the lowest class, who might have been, after a fashion, the Sultana-Validé of this Seraglio. On grand occasions Jean used to distribute largess among the colored population of his neighborhood in the shape of food--bowls of gombo or dishes of jimbalaya. He did it for popularity's sake in those days, perhaps; but in after-years, during the great epidemics, he did it for charity, even when so much reduced in circumstances that he was himself obliged to cook the food to be given away.

But Jean's greatness did not fail to entail certain cares. He did not know what to do with his money. He had no faith in banks, and had seen too much of the darker side of life to have much faith in human nature. For many years he kept his money under-ground, burying or taking it up at night only, occasionally concealing large sums so well that he could never find them again himself; and now, after many years, people still believe there are treasures entombed somewhere in the neighborhood of Prieur Street and Bayou Road. All business negotiations of a serious character caused him much worry, and as he found many willing to take advantage of his ignorance, he probably felt small remorse for certain questionable actions of his own. He was notoriously bad pay, and part of his property was seized at last to cover a debt. Then, in an evil hour, he asked a man without scruples to teach him how to write, believing that financial misfortunes were mostly due to ignorance of the alphabet. After he had learned to write his name, he was innocent enough one day to place his signature by request at the bottom of a blank sheet of paper, and, lo! his real estate passed from his possession in some horribly mysterious way. Still he had some money left, and made heroic efforts to retrieve his fortunes. He bought other property, and he invested desperately in lottery tickets. The lottery craze finally came upon him, and had far more to do with his ultimate ruin than his losses in the grocery, the shoemaker's shop, and other establishments into which he had put several thousand dollars as the silent partner of people who cheated him. He might certainly have continued to make a good living, since people still sent for him to cure them with his herbs, or went to see him to have their fortunes told; but all his earnings were wasted in tempting fortune. After a score of seizures and a long succession of evictions, he was at last obliged to seek hospitality from some of his numerous children; and of all he had once owned nothing remained to him but his African shells, his elephant's tusk, and the sewing-machine table that had served him to tell fortunes and to burn wax candles upon. Even these, I think, were attached a day or two before his death, which occurred at the house of his daughter by the white wife, an intelligent mulatto with many children of her own.

Jean's ideas of religion were primitive in the extreme. The conversion of the chief tribes of Senegal to Islam occurred in recent years, and it is probable that at the time he was captured by slavers his people were still in a condition little above gross fetichism. If during his years of servitude in a Catholic colony he had imbibed some notions of Romish Christianity, it is certain at least that the Christian ideas were always subordinated to the African--just as the image of the Virgin Mary was used by him merely as an auxiliary fetich in his witchcraft, and was considered as possessing much less power than the "elephant's toof." He was in many respects a humbug; but he may have sincerely believed in the efficacy of certain superstitious rites of his own. He stated that he had a Master whom he was bound to obey; that he could read the will of this Master in the twinkling of the stars; and often of clear nights the neighbors used to watch him standing alone at some street corner staring at the welkin, pulling his woolly beard, and talking in an unknown language to some imaginary being. Whenever Jean indulged in this freak, people knew that he needed money badly, and would probably try to borrow a dollar or two from some one in the vicinity next day.

Testimony to his remarkable skill in the use of herbs could be gathered from nearly every one now living who became well acquainted with him. During the epidemic of 1878, which uprooted the old belief in the total immunity of negroes and colored people from yellow fever, two of Jean's children were "taken down." "I have no money," he said, "but I can cure my children," which he proceeded to do with the aid of some weeds plucked from the edge of the Prieur Street gutters. One of the herbs, I am told, was what our creoles call the "parasol." "The children were playing on the banquette next day," said my informant.

Montanet, even in the most unlucky part of his career, retained the superstitious reverence of colored people in all parts of the city. When he made his appearance even on the American side of Canal Street to doctor some sick person, there was always much subdued excitement among the colored folks, who whispered and stared a great deal, but were careful not to raise their voices when they said, "Dar's Hoodoo John!" That an unlettered African slave should have been able to achieve what Jean Bayou achieved in a civilized city, and to earn the wealth and the reputation that he enjoyed during many years of his life, might be cited as a singular evidence of modern popular credulity, but it is also proof that Jean was not an ordinary man in point of natural intelligence.

It may reasonably be doubted whether any other negro of African birth who lived in the South had a more extraordinary career than that of Jean Montanet. He was a native of Senegal, and claimed to have been a prince's son, in proof of which he was wont to call attention to a number of parallel scars on his cheek, extending in curves from the edge of either temple to the corner of the lips. This fact seems to me partly confirmatory of his statement, as Berenger-Feraud dwells at some length on the fact that the Bambaras, who are probably the finest negro race in Senegal, all wear such disfigurations. The scars are made by gashing the cheeks during infancy, and are considered a sign of race. Three parallel scars mark the freemen of the tribe; four distinguish their captives or slaves. Now Jean's face had, I am told, three scars, which would prove him a free-born Bambara, or at least a member of some free tribe allied to the Bambaras, and living upon their territory. At all events, Jean possessed physical characteristics answering to those by which the French ethnologists in Senegal distinguish the Bambaras. He was of middle height, very strongly built, with broad shoulders, well-developed muscles, an inky black skin, retreating forehead, small bright eyes, a very flat nose, and a woolly beard, gray only during the last few years of his long life. He had a resonant voice and a very authoritative manner.

At an early age he was kidnapped by Spanish slavers, who sold him at some Spanish port, whence he was ultimately shipped to Cuba. His West-Indian master taught him to be an excellent cook, ultimately became attached to him, and made him a present of his freedom. Jean soon afterward engaged on some Spanish vessel as ship's cook, and in the exercise of this calling voyaged considerably in both hemispheres. Finally tiring of the sea, he left his ship at New Orleans, and began life on shore as a cotton-roller. His physical strength gave him considerable advantage above his fellow-blacks; and his employers also discovered that he wielded some peculiar occult influence over the negroes, which made him valuable as an overseer or gang leader. Jean, in short, possessed the mysterious obi power, the existence of which has been recognized in most slave-holding communities, and with which many a West-Indian planter has been compelled by force of circumstances to effect a compromise. Accordingly Jean was permitted many liberties which other blacks, although free, would never have presumed to take. Soon it became rumored that he was a seer of no small powers, and that he could tell the future by the marks upon bales of cotton. I have never been able to learn the details of this queer method of telling fortunes; but Jean became so successful in the exercise of it that thousands of colored people flocked to him for predictions and counsel, and even white people, moved by curiosity or by doubt, paid him to prophesy for them. Finally he became wealthy enough to abandon the levee and purchase a large tract of property on the Bayou Road, where he built a house. His land extended from Prieur Street on the Bayou Road as far as Roman, covering the greater portion of an extensive square, now well built up. In those days it was a marshy green plain, with a few scattered habitations.

At his new home Jean continued the practice of fortune-telling, but combined it with the profession of creole medicine, and of arts still more mysterious. By-and-by his reputation became so great that he was able to demand and obtain immense fees. People of both races and both sexes thronged to see him--many coming even from far-away creole towns in the parishes, and well-dressed women, closely veiled, often knocked at his door. Parties paid from ten to twenty dollars for advice, for herb medicines, for recipes to make the hair grow, for cataplasms supposed to possess mysterious virtues, but really made with scraps of shoe-leather triturated into paste, for advice what ticket to buy in the Havana Lottery, for aid to recover stolen goods, for love powers, for counsel in family troubles, for charms by which to obtain revenge upon an enemy. Once Jean received a fee of fifty dollars for a potion. "It was water," he said to a creole confidant, "with some common herbs boiled in it. I hurt nobody; but if folks want to give me fifty dollars, I take the fifty dollars every time!" His office furniture consisted of a table, a chair, a picture of the Virgin Mary, an elephant's tusk, some shells which he said were African shells and enabled him to read the future, and a pack of cards in each of which a small hole had been burned. About his person he always carried two small bones wrapped around with a black string, which bones he really appeared to revere as fetiches. Wax candles were burned during his performances; and as he bought a whole box of them every few days during "flush times," one can imagine how large the number of his clients must have been. They poured money into his hands so generously that he became worth at least $50,000!

Then, indeed, did this possible son of a Bambara prince begin to live more grandly than any black potentate of Senegal. He had his carriage and pair, worthy of a planter, and his blooded saddle-horse, which he rode well, attired in a gaudy Spanish costume, and seated upon an elaborately decorated Mexican saddle. At home, where he ate and drank only the best--scorning claret worth less than a dollar the litre--he continued to find his simple furniture good enough for him; but he had at least fifteen wives--a harem worthy of Boubakar-Segou. White folks might have called them by a less honorific name, but Jean declared them his legitimate spouses according to African ritual. One of the curious features in modern slavery was the ownership of blacks by freedmen of their own color, and these negro slave-holders were usually savage and merciless masters. Jean was not; but it was by right of slave purchase that he obtained most of his wives, who bore him children in great multitude. Finally he managed to woo and win a white woman of the lowest class, who might have been, after a fashion, the Sultana-Validé of this Seraglio. On grand occasions Jean used to distribute largess among the colored population of his neighborhood in the shape of food--bowls of gombo or dishes of jimbalaya. He did it for popularity's sake in those days, perhaps; but in after-years, during the great epidemics, he did it for charity, even when so much reduced in circumstances that he was himself obliged to cook the food to be given away.

But Jean's greatness did not fail to entail certain cares. He did not know what to do with his money. He had no faith in banks, and had seen too much of the darker side of life to have much faith in human nature. For many years he kept his money under-ground, burying or taking it up at night only, occasionally concealing large sums so well that he could never find them again himself; and now, after many years, people still believe there are treasures entombed somewhere in the neighborhood of Prieur Street and Bayou Road. All business negotiations of a serious character caused him much worry, and as he found many willing to take advantage of his ignorance, he probably felt small remorse for certain questionable actions of his own. He was notoriously bad pay, and part of his property was seized at last to cover a debt. Then, in an evil hour, he asked a man without scruples to teach him how to write, believing that financial misfortunes were mostly due to ignorance of the alphabet. After he had learned to write his name, he was innocent enough one day to place his signature by request at the bottom of a blank sheet of paper, and, lo! his real estate passed from his possession in some horribly mysterious way. Still he had some money left, and made heroic efforts to retrieve his fortunes. He bought other property, and he invested desperately in lottery tickets. The lottery craze finally came upon him, and had far more to do with his ultimate ruin than his losses in the grocery, the shoemaker's shop, and other establishments into which he had put several thousand dollars as the silent partner of people who cheated him. He might certainly have continued to make a good living, since people still sent for him to cure them with his herbs, or went to see him to have their fortunes told; but all his earnings were wasted in tempting fortune. After a score of seizures and a long succession of evictions, he was at last obliged to seek hospitality from some of his numerous children; and of all he had once owned nothing remained to him but his African shells, his elephant's tusk, and the sewing-machine table that had served him to tell fortunes and to burn wax candles upon. Even these, I think, were attached a day or two before his death, which occurred at the house of his daughter by the white wife, an intelligent mulatto with many children of her own.

Jean's ideas of religion were primitive in the extreme. The conversion of the chief tribes of Senegal to Islam occurred in recent years, and it is probable that at the time he was captured by slavers his people were still in a condition little above gross fetichism. If during his years of servitude in a Catholic colony he had imbibed some notions of Romish Christianity, it is certain at least that the Christian ideas were always subordinated to the African--just as the image of the Virgin Mary was used by him merely as an auxiliary fetich in his witchcraft, and was considered as possessing much less power than the "elephant's toof." He was in many respects a humbug; but he may have sincerely believed in the efficacy of certain superstitious rites of his own. He stated that he had a Master whom he was bound to obey; that he could read the will of this Master in the twinkling of the stars; and often of clear nights the neighbors used to watch him standing alone at some street corner staring at the welkin, pulling his woolly beard, and talking in an unknown language to some imaginary being. Whenever Jean indulged in this freak, people knew that he needed money badly, and would probably try to borrow a dollar or two from some one in the vicinity next day.

Testimony to his remarkable skill in the use of herbs could be gathered from nearly every one now living who became well acquainted with him. During the epidemic of 1878, which uprooted the old belief in the total immunity of negroes and colored people from yellow fever, two of Jean's children were "taken down." "I have no money," he said, "but I can cure my children," which he proceeded to do with the aid of some weeds plucked from the edge of the Prieur Street gutters. One of the herbs, I am told, was what our creoles call the "parasol." "The children were playing on the banquette next day," said my informant.

Montanet, even in the most unlucky part of his career, retained the superstitious reverence of colored people in all parts of the city. When he made his appearance even on the American side of Canal Street to doctor some sick person, there was always much subdued excitement among the colored folks, who whispered and stared a great deal, but were careful not to raise their voices when they said, "Dar's Hoodoo John!" That an unlettered African slave should have been able to achieve what Jean Bayou achieved in a civilized city, and to earn the wealth and the reputation that he enjoyed during many years of his life, might be cited as a singular evidence of modern popular credulity, but it is also proof that Jean was not an ordinary man in point of natural intelligence.

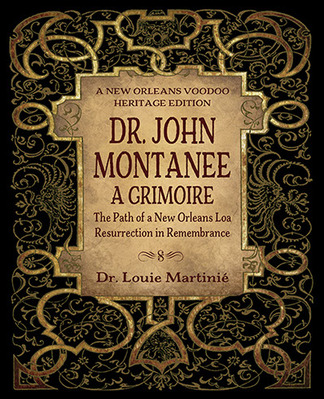

Dr. John Montanee: A Grimoire

by Dr. Louie Martinie

The first book length publication celebrating the life and times of the first Dr. John (birth circa 1815 - passing 1885), this publication contains conjures meant to offer Dr. John the opportunity to become a fully present loa in today’s world.

History and folklore have Dr. John filling many posts. He was a freeman of color reputed to be a contemporary of Marie Laveaux in the voodoo on Congo Square, a New Orleans conjure man, drummer, herbalist, physician, and spiritual Doctor as well as having a coffeehouse and dealing in real estate. He was a man worth knowing and is a spirit worth working with.

Reprints of the actual historical documents include a contract with Dr. John’s signature, his Marriage Certificate, his Death Certificate, and various censuses from the period providing important keys to his life. Folkloric sources of beliefs about Dr. John, both verbal and written, are extensively treated. An index and a bibliography add to the book’s ease of use.

A unique feature of the book consists of experiments, explorations, experiences, investigations, teachings, and conjures by current members of the spiritual community which are provided to bring the reader closer to Dr. John and Dr. John closer to the reader. The collection of this material is ongoing through DrJohnVoodoo.com and the reader is encouraged to participate in this great work.

This book is a comprehensive reference for the study of Dr. John as well as the offering of service to the Good Doctor. So often it is heard that little is published on Dr. John. Now that is no longer the case.

by Dr. Louie Martinie

The first book length publication celebrating the life and times of the first Dr. John (birth circa 1815 - passing 1885), this publication contains conjures meant to offer Dr. John the opportunity to become a fully present loa in today’s world.

History and folklore have Dr. John filling many posts. He was a freeman of color reputed to be a contemporary of Marie Laveaux in the voodoo on Congo Square, a New Orleans conjure man, drummer, herbalist, physician, and spiritual Doctor as well as having a coffeehouse and dealing in real estate. He was a man worth knowing and is a spirit worth working with.

Reprints of the actual historical documents include a contract with Dr. John’s signature, his Marriage Certificate, his Death Certificate, and various censuses from the period providing important keys to his life. Folkloric sources of beliefs about Dr. John, both verbal and written, are extensively treated. An index and a bibliography add to the book’s ease of use.

A unique feature of the book consists of experiments, explorations, experiences, investigations, teachings, and conjures by current members of the spiritual community which are provided to bring the reader closer to Dr. John and Dr. John closer to the reader. The collection of this material is ongoing through DrJohnVoodoo.com and the reader is encouraged to participate in this great work.

This book is a comprehensive reference for the study of Dr. John as well as the offering of service to the Good Doctor. So often it is heard that little is published on Dr. John. Now that is no longer the case.

CONTENTS

Festival Teachings, Conjures, and Magickal Records

Experiments, Explorations, Experiences, and Conjures

Investigations

Visit drjohnvoodoo.com for more downloads of historical documents well-suited for use as talismans, and to read Voices of the Communities and to purchase the book direct from Black Moon Publishing.

- Beginning at the Destination

- First Conjure: The Pelican

- Second Conjure: Speaking in the Voice

- Third Conjure: A Conjure Ball

- History: Links and Talismans

- Folklore: Links and Pathways

- Voices of the Community: Experiments, Explorations, Experiences, Investigations, Teachings, and Conjures

Festival Teachings, Conjures, and Magickal Records

- Gryphon’s Nest Festivals, Louisiana

- Starwood Festivals

- Babalon Rising Festivals

Experiments, Explorations, Experiences, and Conjures

- Always Listen to the Doctor by Claudia Williams

- Dr. John Montanee: The Physician’s Message is Know Thyself by Lilith Dorsey

- Gris Gris Lamp for Dr. John Montanee by Denise Alvarado

- To Sleep On The Tomb of Dr. John Montenet by Witchdoctor Utu

- Notes on the Painting of The Tomb of Doctor John by Linda Falorio

- Bringing Balance to the Order of Voodoo Religion by Priestess Miriam

- The Elevation of Dr. John Montane by Andrieh Vitimus

- Some Conjures by Louie Martinié

- A Dream and a Ritual Record by Maegdlyn

- You Can be a Healer Now by Baron Sylvia

- He Walked From His House by Houngan Steven Denney

- A Dream by Pamela Marie Nemec

- Drum Needed to be Played by Midnyte Hierax

- Sweet, Sweet Water 2012 Babalon Rising Festival: Conjure by Sara Terry

Investigations

- Bright's Disease: A Medical Investigation by Sara Grey

- The Superposition of Dr. Jean: A Handwriting Investigation by Denise Alvarado

- Dr. John Montanee: An Astrological Riddle by Rev Bill Duvendack

- Dr. John's Natal Astrological Chart by Rev Bill Duvendack

- Dr. John's Marriage Progression Astrological Chart by Rev Bill Duvendack

- Sonick Sigil: Drumming Dr. John’s Name by Vovin Lonshin and Louis Martinié

- The Spiritual Doctors of New Orleans

- Ending at the Beginning: Why - An Apologia

- New Orleans: A Voodoo Pilgrimage

Visit drjohnvoodoo.com for more downloads of historical documents well-suited for use as talismans, and to read Voices of the Communities and to purchase the book direct from Black Moon Publishing.

Some Sample Talismans

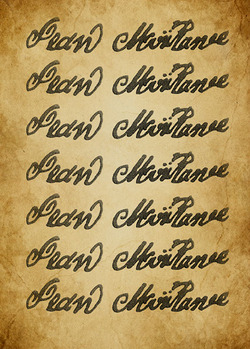

Historical documentation of Dr. John's signature.

Historical documentation of Dr. John's signature.

Dr. John's Signature

The image to the left is an enlargement of Dr. John Montanee’s signature. It can be used as a talisman in conjures opening the path to communication with Dr. John. "I would deeply recommend not asking anything of Dr. John in these communications. Simply, freely offer what you can. The Good Doctor will respond" (Louis Martinie, 2014).

For more historical documents that can be used as magical talismans, please visit drjohnvoodoo.com.

The image to the left is an enlargement of Dr. John Montanee’s signature. It can be used as a talisman in conjures opening the path to communication with Dr. John. "I would deeply recommend not asking anything of Dr. John in these communications. Simply, freely offer what you can. The Good Doctor will respond" (Louis Martinie, 2014).

For more historical documents that can be used as magical talismans, please visit drjohnvoodoo.com.

Historical record of Dr. John Montenee's occupation.

Historical record of Dr. John Montenee's occupation.

Record of his Occupation

Records only the “Profession, Occupation, or Trade of each Male Person.” Females not recorded. This is the milieu in which Marie Laveau worked and lived.

For more historical documents that can be used as magical talismans, please visit drjohnvoodoo.com.

Records only the “Profession, Occupation, or Trade of each Male Person.” Females not recorded. This is the milieu in which Marie Laveau worked and lived.

- Columns 11 and 12 emphasize literacy. Dr. John worked on writing his name (A New Orleans Voudou Priestess, Carolyn Morrow Long, University Press of Florida, p. 145).

- Philippe is a son.

- In this period, “coffeehouse” could be a euphemism for brothel.

- The present Dr. John (John “Mac” Rebennack, Jr) said, “I actually got a clipping from the Times Picayune newspaper about how my great-great-great-grandpa Wayne was busted with this guy for runnin’ a voodoo operation in a whorehouse in 1860. (Wiccapedia) ” The date of this document is 1850, this is an interesting collaboration of the Present Dr. John’s account.

For more historical documents that can be used as magical talismans, please visit drjohnvoodoo.com.